Everyone knows when we post online, we’re being watched. The NSA, the FBI, Google, Facebook, Apple, Visa, ModCloth–they monitor our online activities for patterns that indicate danger or that can teach them to market directly to us; they monitor for aberrant behavior that needs correction or attention, or that can be profited by. But, we are also always monitoring each other: it’s a miniature (or major) scandal whenever someone posts on Facebook or Twitter about their experiences that deviate from social norms. Who’s drunk the night before a final? Who’s already Facebook-married to her boyfriend of one week? Or even just, Who doesn’t understand the conventions of what it’s okay to post–Who’s being too boring? With the spread of social media came the spread of an Internet culture, and the heart of that culture is social. We Internet-goers are a society.

Like any society, there are norms and values that are reinscribed and reinforced by both our own behavior and the ways that we monitor the behavior of others. American Internet culture is largely derived from, of course, American offline culture–although can we really separate them? Thinking about social media–really, the social Internet–as the major vehicle by which we watch each other, I’m arguing here that social media can be read as Foucault’s confessional-turned-panopticon, in which people expose and put into language (text, pictures, videos, music) their experiences and stories, the process of which makes them subject those experiences to social discourse, to become “subjects,” to self-police and be policed in terms of the social norms and values of those watching from the tower–the confessors, the public, society. By “confessing” publicly, we enter into a social relationship of watching, surveilling, policing one another.

Jeremy Bentham originally proposed the idea of the panopticon: a circular prison, with one cell for each individual, one tower in the center, and no way to see into the other cells or the tower. From the tower, an officer or council might be stationed to watch all of the prisoners, and with this constant threat of being watched–and the subsequent threat of punishment if they do wrong–prisoners will follow rules by their own will.

In Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault considers the implications of this prison model, as well as provides a route for thinking about a panopticon without the walls–a socially-, institutionally-enforced panopticon in which we are all imprisoned. As power became disembodied, democratized, removed from the singular monarch, and punishment moved into the prisons, the power to discipline and control bodies became institutionalized. Prisoners can be constantly watched, timed, instructed, and re-interpolated into correct behavior according to social norms. Here, prisoners are taught how to be “good” citizens by teaching them how to monitor themselves: “He who is subject to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power;…he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles” (Discipline & Punish III.3). And, when the panopticon extends out of the prisons and into society, it is not “Big Brother” that we need to worry about, but, as Tom Brignall III says, “‘Little Brother’ (or other inmates).”

Several authors have considered the role of the Internet as panopticon, especially thinking about the relationship between information, knowledge, and power, but their analyses largely rest on the concern that the government and corporations have the power to occupy the tower. Especially with the recent leak of NSA intelligence-gathering methods, fears are stronger than ever about the potential that these powerful institutions have in watching us.

More disconcerting than official authorities’ seizing information, however, is the voluntary nature of disclosing ourselves online, of making ourselves visible for surveillance. In 1997, James Boyle articulated the “Holy Trinity” of the Internet, three principles which still serve as the basis of Internet culture:

“The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.”

“In Cyberspace, the First Amendment is a local ordinance.”

“Information Wants to be Free.”

Reading very much like aphorisms in Dave Eggers’ The Circle, this trinity asserts that freedom of expression–and thus, of sharing oneself–is key online. What I want to focus on here is not the government’s ability to watch us–maybe because I’m a member of the 9/11 generation, that doesn’t bother me all that much–but, our ability and desire to put ourselves in the panopticon and then watch one another; we are in a two-way panopticon.

Thinking about what I’m calling the myth of free expression online also brings us to the repressive hypothesis, and to confession. Later in his life, Foucault wrote The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, and in it, he debunks the repressive hypothesis–the idea that discourse on sex has been repressed and censored, and every time we talk about sex we are resisting that force. Instead, he argues that we have always been encouraged to talk about sex in more and more prescribed ways so that our experiences can be pulled out into the open, so they can be surveilled and recorded, monitored and policed, while encouraging a similar kind of self-policing as the panopticon. Power is not only negative, prohibitive, but power can be wielded through the “incitement to discourse,” about sexuality in this history, but also about all experiences. This discourse was encouraged first in the the Catholic Church in the confessional, later by doctors, psychiatrists, and even later still, by talk show hosts when it was joined with our love of celebrity. Incitement to discourse encouraged confession of sexuality down to the details, while also regulating where and when it was appropriate to speak about sex, and in what terms. By making sex an important–the important–experience to talk about, the institutions in power made it simultaneously known and secretive/repressed (since it then became liberatory to speak from under repression) (19). Foucault says this was, “the nearly infinite task of telling–telling oneself and another, as often as possible, everything that might concern the interplay of innumerable pleasures, sensations, and thoughts” (20). And, this telling was incited not for self-indictment of illegal acts, but for self-improvement at the level of desire:

Western man has been drawn for three centuries to the task of telling everything concerning his sex; that since the classical age there has been a constant optimization and an increasing valorization of the discourse on sex; and that this carefully analytical discourse was meant to yield multiple effects of displacement, intensification, reorientation, and modification of desire itself (23).

While the repressive hypothesis argues that confessions were made “apart from or against power,” Foucault points out that they took place “in the very space and as the means of its existence” (32). Confession, the first person narration of experience, was constructed as a good, as an extraction of truth from oneself and subsequent self-examination, so that we do not recognize it as a working of power, but we see it as if truth “demands” surfacing. We bring out the writer through her narrative, through her confession, while constraining, prohibitive power tries to keep the truth inside that writer, but in confessing, we constitute ourselves “as subjects in both sense of the word” (60). Thus, experience is institutionalized, “constrained to lead a discursive existence” (33).

The confession inherently unfolds within a power relationship, the confessant confesses to the confessor, who holds the authority to require the confession. In the case of the internet, that is the public, and there is no explicit power relationship, but instead a much more subtle power of authority, in which “confessions” online are not required but expected, and then the public has the power to judge, to discipline, to shun, to absolve. But, the confessional discourse always originates “below,” in the confessant, acting on that expectation and the desire to change desire. As in Discipline & Punish, Foucault recounts the democratization of power; though we still conceive of power as monarchical–invested in a powerful individual and prohibitive–it is actually the public, society, the institutions–the internet as an institution–that hold power. We understand the expectation of the digital age, the myth of free expression, that we must confess, and, “the irony of this deployment is in having us believe that our ‘liberation’ is in the balance” (159).

Simon Copland thinks about our “culture of confession,” and, like those who think about the internet-as-panopticon, he limits himself to worrying about government and corporate access to information provided by these confessions, like on “personal diaries posted on the Internet” (Capp in Copland). In 2014, personal diaries, personal confessions, are tailored to apps that are specifically made to post and read confessions/watch and be watched–Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, blog platforms. Social media incites us to discourse about our experiences, encourages us to tell our stories, while also asking us to revise our “desires,” our experiences of those stories, to fit with what will be acceptable to our confessors. And, by making these confessions publicly, we place ourselves into that two-way panopticon, whereby anyone online can watch us, so we similarly self-police, but we can also watch anyone else; we become both instruments and subjects of interpolation ourselves.

The most obvious place to look for the digital confessional is the literal one: confession websites and blogs, and confessions made more generally around the web. Jenny Hollander writes about this confession video that went viral last fall, in which Matthew Cordle confesses to drunk driving the wrong way on a highway and killing a man, and promises that he will take responsibility for his crime:

Hollander points out that this is only one more confession of a gruesome crime that the anonymity of the internet allows to be glorified. Cordle got to share his confession, as the myth of free expression says he should. If the internet is a place for open expression, for stories, shouldn’t people be able to reveal those stories that they most need to tell? Of fights, of rape, of murder? If the victims speak, so shouldn’t the victimizers? If one anonymously confessed to priests before, why shouldn’t she seek absolution in the new, digital confessional? Between PostSecret, Reddit, and numerous other confession websites, Tumblrs, Facebook pages, there are so many social venues wherein people can make their confessions, but in making these confessions, they are also confessing in a Foucauldian sense. By sharing anything from a dark, criminal secret, like Cordle did, to sexual fantasies of a fictional character (NSFW), to problems with school, these confessants are not only making these “secrets” available publicly–and thus, they might think, resisting censorship or repression–but they are making them available for policing. On an SJU Secrets confession, fellow students may comment in agreement, or they might shame the o.p./confessant for being racist or a slut. And, in posting, confessants understand the social expectations of these confessions. Maybe they’re bragging about that secret, but maybe their “conscience” is getting to them; maybe they feel that they need to share this story and face the denouncement or forgiveness of the Internet community, of society. By telling their stories, these confessants are making their experiences discursive, to be read, to be shaped and understood through social norms and values, and to be disciplined and corrected if deviating from those norms and values.

Another aspect of these confession sites is their anonymity. Posting anonymously, of course, makes the confessant feel more secure from the hate or discipline that might come their way, but at the same time, I’m not sure that anonymity really defeats the function of confession simply because the confessant is not attached. What is being read/watched/surveilled is not particularly the subjectivity of that confessant, but their actions, their stories–in other words, their role as a subject of discussion and of institutions rather than their role as a subject of choice, action, identity. However, this also raises the question whether one’s Internet identities/presence is ever truly not anonymous–one may post under her name, but it is still detached from her person. Perhaps the inherent anonymity of the Internet allows for confession to take its current, ubiquitous form.

So, turning to non-anonymous forms of digital confession, we turn to the big three: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. There are, of course, the more explicit kinds of non-anonymous confession: there was the man who posted a picture of his wife’s corpse on Facebook with the caption “Im going to prison or death sentence for killing my wife love you guys miss you guys takecare Facebook people you will see me in the news,” and there are those who “TweetWhatYouEat” in order to manage their caloric intake by inviting and self-administering the shame of making bad choices public.

But, really, every social media post is a confession. Every time that you or I post a status, a tweet, a picture, a blog entry, we are putting our experiences into social discourse, we are self-policing according to what will be acceptable to our followers and friends, and we are creating a record of information about us, by all of which, we subject ourselves to social norms. While most feedback from friends is usually affirmative, it is so because we have tailored our story to their affirmation; we have experienced, then shaped that experience for confession, for discourse. We try to be funny, we try to be smart, we try to be cool; we choose what we would like to share based on creating both an image and an actual self that are in-line with what the Internet public wants–and yet, we do not choose in many ways, because these confessions are expected/required.

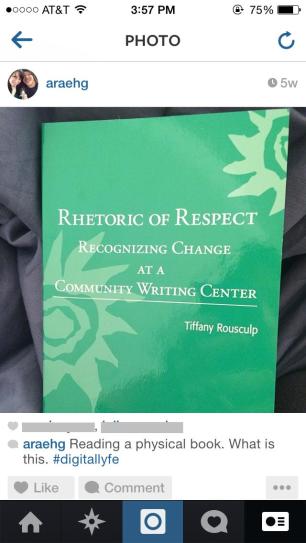

In the Instagram screenshot above, I posted a pictorial confession. My confession: that I am reading Tiffany Rousculp’s Rhetoric of Respect; that it is an academic book, for a class; that I am engaging with Writing Center scholarship; that I am reading this book in print, rather than digitally; that I am not used to reading print anymore; that I usually read digital texts; that I think it’s uncool to have to read in print; that I am embracing a digital identity. This confession also reveals some of my personality: I am academic, I am sarcastic, I am modern, I am progressive and quick to accept new forms of activities, and I am not all that funny but I try (feel free to disagree in the comments). With this post, I tell my experience, my story, but I also tell myself, to my followers. And, this post fits into a larger story of my daily life that I confess online through Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google Plus, and even my own e-portfolio website. In this way, I am not only making myself available for surveillance, but I am self-policing toward the self that the Internet wants me to be.

When I confess, I am really making myself Transparent. The world of Eggers’ The Circle turns on the idea of Transparency and Going Transparent–a person wears a live-streaming camera around her neck at all times, so that everything she does, everyone she speaks to, and even many of her thoughts as she narrates her transparency, are available to viewers online. In addition, thousands of SeeChange surveillance cameras are placed in public locations over the course of the novel, making all of those locations transparent, but, more importantly, providing another layer of transparency for those who Go Transparent. (To see an ongoing Transparency experiment, visit Jaedah Carty’s blog here.) The Circle’s utopia is a world in which everyone is transparent, so that there are no more secrets, lies, or stories to confess–everyone is confessing themselves all the time. In a world that already has SeeChange-style surveillance and in which we are making ourselves transparent via social media, we are close to this utopia, which is truly a Foucauldian nightmare.

But, going transparent does not have to be the end of freedom. Instead, as I have shown in this post, we are already unfree in so many ways–our confessions put us on display in a digital panopticon, and we are already purveyors of hegemonic social norms when we occupy the tower for other inmates/confessants. We do not resist by sharing our stories; we share them as the very basis upon which our power relationships are structured. In this digital age, as we become more transparent, we need to ask ourselves what our privacy is worth. What is the fault in surveillance, in confession, in policing and self-policing? What is at stake?

In Stephen Davenport Jukuri’s chapter in Stories from the Center, he mentions Foucault’s Voices of Inclination and Institution. Using the first, one fools herself into believing she is working outside institutionalized norms and power structures–she is freely expressing herself online, in a culture based on the first amendment. Using the second voice, she assimilates to and accepts those institutionalized norms and power structures, taking the path of least resistance. In reality, using both voices, one might say the same thing. Instead, Jukuri says that there is a possibility for a “third voice:”

“It would be a voice that can learn to work between those two extremes, to facilitate a mutual negotiation between the individual and the institution, working with individuals not only to occupy and employ a multitude of subject positions but to gain some control over their construction, to negotiate their terms, to re-create them, and to open up new fields of possibilities for ourselves and each other” (60, emphasis mine).

A friend named this the Voice of Acknowledgement, in which one is aware of the Institution and the Inclination and their false binary opposition to one another, and learns to not only work between and among them but to make them both work for her.

We are usually given two options online: we can fit ourselves to the confessions demanded by social media, accept the privacy settings as they are, and embrace our subject positions OR we can resist, and create groups that value and privilege an open kind of communication, art, creativity, experience. These are not necessarily mutually exclusive–that is the myth–and maybe Acknowledgement of the interplay between the two, Acknowledgement of the ways in which inclinational expression is institutional, and institutional expression is inclinational, can create a middle-space, a “third voice,” a space of negotiation and re-creation that allows us to live as freely as we can within the digital confessional, the virtual panopticon.